In the old days, the Great Sage, Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, made havoc in Heaven and frightened a hundred thousand celestial soldiers; in these latter days, though, he discovered there were mortals who could do something still more vexing than this: They could put an image of him between two fingertips and call it a card.

It happened in the Northern Capital, under a sky the color of diluted ink. The Great Sage Equal to Heaven perched on the rooftop of a high building, his feet dangling above a river of carriage-lights. Below him, Beijing hummed like a beehive. Above him, the moon hung low, a thin sliver in a darkened sky.

He sniffed once, and the smell of incense—the kind found in many of the temples below—led him to a narrow hutong where gray bricks sweated winter damp. There, behind a lacquered door, a young woman sat at a low table with a book open before her. On its pages lay not sutras but cards—rectangles of stiff paper, each with a picture that was not quite a picture, because each of those cards seemed to breathe.

The Great Sage’s eyes narrowed.

“That scent is mine,” he said, “and yet it is not mine.”

He vanished from the roofbeam and appeared, without even a whisper of moving cloth, in the shadow behind the young woman’s screen. He leaned forward. The cards lay in rows of two by two, like military officers awaiting inspection.

There were strange beasts: a dragon coiled like calligraphy, a fox with tails folded like fans, a hunched thing that might once have lived in a mountain spring. Each card had a faint halo, as though the paper had been cut from moonlight.

Then he saw it.

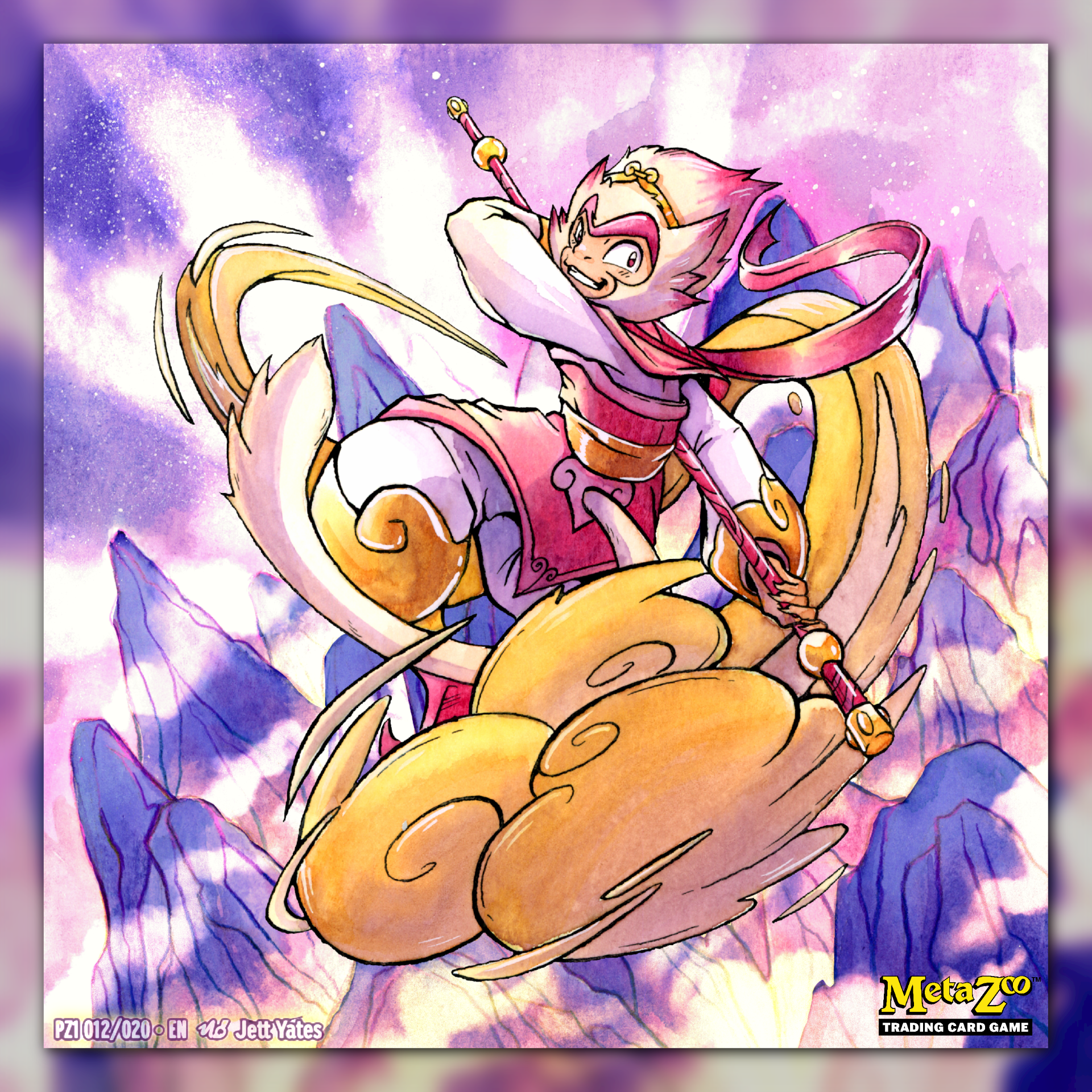

On one card, ink and light had caught the outline of a monkey wearing a golden headband, crouched as if ready to spring, one hand braced on a staff that could be a mountain or a needle depending on his mood. The eyes—those were the most surprising—were not drawn. They looked back.

Sun Wukong forgot, for half a breath, to be angry.

He stepped out from behind the screen as though stepping from one tale and into another, and he said, “Who dares paint the Great Sage without asking him to pose?”

The young woman did not shriek, as he expected. She did not spill tea. She turned her head calmly, like someone who had been anticipating a guest at a particular hour.

She was perhaps twenty, her hair tied back, her sleeves plain, her gaze as sharp as the edge of a newly honed blade. A small charm of red thread circled her wrist. A spellbook lay open under her palm as if it were a family register or a holy tome with guidance already familiar to her.

She rose, cupped her hands, and bowed—not deeply but correctly. “Great Sage,” she said in clear Mandarin that even a monkey from Flower-Fruit Mountain would approve, “you came sooner than I expected.”

“So, you knew I would come.” Sun Wukong strode to the table and tapped the corner of the card with one fingernail. It shivered under his touch, as though it had nerves. “Explain this.”

The young woman’s name, as she gave it, was Mei Lin—two syllables even a foreigner could catch and a name that sat on the tongue like both plum blossom and forest shade.

“I did not paint you,” Mei Lin said. “I mapped you.”

At that, the Great Sage’s laughter snapped like a whip. “Mapped? Do you think I am a mountain path for travelers? A river to be measured? I am the Great Sage Equal to Heaven.”

Mei Lin met his glare without flinching. “Exactly,” she said. “You are too vast to be held whole. Mapping takes only a dust mote. An invisible spark of essence—your inner self that makes you you. I took that spark, and I mixed it with an equal spark of myself. The two together made…this.”

She nodded toward the card.

Sun Wukong leaned down until his nose almost touched it. The mapped Sun Wukong on the card leaned down too, mirroring him with irritating precision. They were nose to nose.

The Great Sage’s mouth twisted. “It copies my posture.”

“It copies what you show,” Mei Lin said, “not what you are entirely.”

Sun Wukong’s eyes gleamed. “You stole my essence.”

“I borrowed it,” Mei Lin replied, “after you insisted.”

“I insisted?” He straightened so fast that the candle flame bent away from him. “Little girl, you have mistaken a monkey for a fool.”

Mei Lin smiled. “It was not difficult.”

This was insolence. This was also, Sun Wukong grudgingly admitted, interesting.

He threw himself into a chair as if it were his throne, and he crossed his legs. “Then tell me, Miss Plum-Forest, how did you make me ‘insist’ on being mapped?”

Mei Lin did not hesitate—it was as though she had rehearsed the confession as one rehearses a poem.

“I told a story,” she said.

Sun Wukong snorted. “Everyone tells stories about me.”

“Yes,” she said, “and most are wrong in the details. I told one that was correct.”

She lifted her hand and traced the air, and a thin ring of light appeared—like the golden band on his head but smaller, hovering above the table.

“I said,” Mei Lin continued, “that the headband was not merely a punishment from the Buddha. I said it was also an instrument: a circle that remembers the shape of the wearer’s mind. I said that if one could press the Great Sage’s ego through that circle—gently and with praise—one might catch the essence as one catches a seal on ink.”

Sun Wukong’s ears twitched.

“And you,” Mei Lin added, “could not bear the thought of a mortal understanding your headband better than you do.”

The Great Sage grinned, showing teeth. “So, you praised me, and then you dared me.”

“I asked you,” she said, “to demonstrate your ‘true self’ in a single breath. I said no one living could grasp it. You laughed. You agreed. You performed one of your transformations—so quick, so complete—that your essence flared like a spark struck from flint.”

Sun Wukong’s fingers tightened on the chair arms.

“And in that instant,” Mei Lin finished, “I mapped you.”

He stared at her. She stared back. Between them lay the card, innocent as paper, guilty as theft.

At length, Sun Wukong said, “You are either very brave or very foolish.”

Mei Lin bowed again. “In Beijing, those two are sisters.”

The Great Sage barked a laugh despite himself. Then his face grew serious.

“Give it to me,” he said, pointing at the card.

Mei Lin’s fingers slid, almost affectionately, over the edge of the card, as one might stroke a caged, helpless pet. “I cannot.”

Sun Wukong leaned forward. “Cannot? Or will not?”

Mei Lin’s eyes flicked to her spellbook. “This mapped card is bound to me and to my book. If you snatch it, you will shatter it like crystal glass and spill the essence inside. Yours will scatter. Mine will bleed. Neither of us will like the result.”

Sun Wukong’s gaze sharpened. This was not the stammering excuse of a frightened thief. Though he wondered how much of the truth she adjusted to suit her argument, what she said had the ring of rules—rules he despised but respected enough to exploit.

“So,” he said, “you have a net I cannot break without dirtying my fur.”

Mei Lin nodded. “If you want it, you must obtain it properly.”

Sun Wukong’s eyes sparkled. “Properly? Since when did the Great Sage do anything properly?”

Mei Lin’s smile widened a hair. “Since the Buddha put a hoop around your head.”

A nerve jumped in Sun Wukong’s temple. Then, slowly, he sat back, and his anger turned—like a wheel turning in the dirt—to delight.

“Very well,” he said. “Let us play the game of ‘proper.’ I will take my card without shattering it or harming your book. And you will hand it to me with your own fingers.”

Mei Lin folded her arms. “How?”

Sun Wukong lifted one finger. “A riddle.”

Mei Lin raised an eyebrow. “A riddle?”

“In the old days,” Sun Wukong said, “monks and demons traded riddles as they traded blows. Listen carefully, little caster. If you cannot answer, you must give me what I ask.”

Mei Lin’s eyes glittered with interest. “And if I answer?”

Sun Wukong grinned. “Then I will give you what you ask—within reason.”

“Within reason,” Mei Lin repeated, as though tasting whether the words had holes.

Sun Wukong began, and his voice took on that half-singing cadence of old storytellers:

“I am born from your hand, yet I can bind your hand.

I am made of two, yet I show only one.

I am a picture that is not a picture, a gate that is not a gate.

If you keep me, you keep trouble; if you give me, you keep power.

What am I?”

Mei Lin’s gaze dropped to the cards. Her fingers hovered over her spellbook. For a moment, the only sound was the distant hiss of traffic like a dragon breathing through a sewer grate.

“A mapped card, of course,” she said at last.

Sun Wukong’s grin did not move. “Close but too broad.”

Mei Lin frowned. “A mapped essence.”

“Closer still.” Sun Wukong waggled his finger. “But still a basket that holds too many fruits.”

Mei Lin inhaled. “The binding between caster and cryptid.”

Sun Wukong’s eyes shone. “Now you are sniffing the right tree.”

Mei Lin’s lips pressed together. “Then… the answer is ‘the name’?”

Sun Wukong laughed, and the mapped monkey on the card laughed too, albeit silently. “Ah! You are clever, Plum-Forest. But the name is only a hook; the fish is something else.”

Mei Lin’s gaze sharpened. “Then tell me.”

“No,” Sun Wukong said cheerfully. “That is not how riddles work. You have three guesses. And now, you have used them.”

Mei Lin’s face did not fall. Instead, she said, “You’re cheating.”

“Of course,” Sun Wukong replied. “I am Sun Wukong.”

Mei Lin’s eyes narrowed, and she glanced down at the card again, at the ink-monkey that stared up with its own fierce amusement.

Then Mei Lin said something that made Sun Wukong’s laughter pause mid-bounce.

“The answer is ‘ego.’”

Sun Wukong blinked.

Mei Lin spoke quickly, like someone racing a closing door. “Born from my hand—I used my hand to stroke yours, to flatter, to provoke. Yet it binds my hand—now I cannot act freely because you’ve come for it. Made of two—your essence and mine—yet it shows only one. Your face on the card. Keep it, keep trouble—your trouble. Give it, keep power—because the power is in the act of mapping, not in the paper. The gate that is not a gate—because the card opens a path to summon, but it is not a true body. The picture that is not a picture—because it contains a self. Ego fits all of it.”

The candle flame trembled. Outside, a bicycle bell rang as if announcing a victory.

Sun Wukong stared at Mei Lin with fresh appraisal. Then he clapped his hands, delighted. “Excellent! You are not merely a thief; you are a scholar.”

Mei Lin’s shoulders loosened. “So, I win?”

The Monkey King leaned forward and spoke softly. “You win… another riddle.”

“That was not the agreement.”

Sun Wukong’s grin returned, shameless. “Ah, but you answered my riddle, not the riddle.”

Mei Lin’s jaw tightened. “There was only one.”

Sun Wukong lifted the card between two fingers—so quickly she did not see when his hand moved, only that it was suddenly there. He held it up, and the mapped Sun Wukong looked at him with the same cocky tilt of the chin.

“Wrong,” he said. “There were two. One I spoke aloud. The other I spoke with my eyes.”

Mei Lin reached out, but her hand stopped short of the spellbook, as if invisible thorns guarded it.

Sun Wukong continued, almost kindly: “You guessed ‘ego.’ That is, indeed, the answer to the riddle of how you caught me. But it is not the answer to what I asked.”

Mei Lin’s brow furrowed. “Then, what did you ask?”

Sun Wukong tapped the card. “I asked: What am I? Not what is this paper, not what is your method. What am I, now that you have done this thing?”

Mei Lin’s mouth opened but then closed.

Sun Wukong’s voice took on a mischievous lilt. “You see? Even clever people trip when they hurry.”

Mei Lin’s gaze locked on the card in his fingers. “Give it back.”

Sun Wukong shook his head. “Not yet. First, I will look.”

He held it closer. The mapped Sun Wukong’s eyes stared up at him with a strange steadiness, neither fully alive nor fully dead. It was like seeing his reflection in a pond but a reflection that did not belong to him.

Sun Wukong’s intellect, steady as his staff, prodded at the thing.

“So,” he murmured, “a mortal has taken a grain of my mountain and mixed it with a grain of her own soil. This is what grows.”

He frowned, not in anger but in curiosity. “You did not capture my strength whole. If you had, this card would have burst into flame and your book would have turned to ash. No—you captured my tendency. My direction. My taste.”

Mei Lin watched him warily. “It’s still you.”

Sun Wukong snorted. “It is like me in the way a shadow is like a man. Useful, but you cannot eat with it. You cannot bleed with it. Yet a shadow can frighten children and confuse fools.”

He looked up at Mei Lin, eyes bright. “Tell me, Mei Lin. When you call this mapped self… does it obey you?”

Mei Lin hesitated. Then, honestly: “Not exactly.”

Sun Wukong laughed. “Good.”

Mei Lin’s cheeks warmed. “It follows the guideline I write. But it twists it. It argues. It finds loopholes.”

Sun Wukong nodded as if pleased. “Then the essence you took is the right one.”

“You’re proud.”

“Why shouldn’t I be? Even my twin refuse to be twins.”

He flicked the card lightly. The mapped monkey flicked its staff in response, as if impatient.

Then Sun Wukong said, “Now—about your card.”

“Yes?”

Sun Wukong’s face grew solemn—so solemn that if one did not know him, one might be fooled.

“In the old days,” he said, “I was given a title: Great Sage Equal to Heaven. It was a lie but a flattering one. And I accepted it, and it led me into trouble.”

Mei Lin listened, cautious.

“In these days,” Sun Wukong continued, “you have given me a new title: Mapped One. It is also a lie. And yet…”

He held the card out toward her.

Mei Lin’s eyes widened. Her hand moved, uncertain. “You’re returning it?”

Sun Wukong’s mouth twitched. “You want it, don’t you? You want the Great Sage in your book. You want to say you mapped Sun Wukong, and I know of no other caster who can boast the same.”

Mei Lin’s pride flickered. “Nor do I. Yes, this is what I want.”

“Then take it. But first, we will trade.”

Mei Lin’s suspicion returned. “Trade what?”

Sun Wukong spread his hands. “You said you mixed my essence with yours. Half and half. Very fair. So now I will take back my half.”

Mei Lin stiffened. “You can’t.”

Sun Wukong smiled sweetly. “You believe I cannot. That is why you will let me.” He pointed at the spellbook. “Open to the page where you determined my guideline.”

Mei Lin hesitated. Then she did it. On the margin beside the card’s place, she had written in careful characters a rule that anchored her mapping:

Summon the Great Sage as guardian and trickster. He must not harm the caster.

Sun Wukong clicked his tongue. “Ah. You bound my shadow with kindness. Clever. But you left a door open.”

Mei Lin frowned. “Where?”

Sun Wukong tapped the last phrase with one fingernail. “You wrote: He must not harm the caster.”

“Yes.”

Sun Wukong’s eyes gleamed. “Little Plum-Forest. You assumed harm means injury. Blood. Broken bones. But harm is broader than that. Harm can be insult. Harm can be debt. Harm can be loss of face.”

“That’s not fair.”

“Not fair? Welcome to the mountain.”

The Monkey King leaned in and spoke in a whisper that carried power, like a mantra spoken backward. “Repeat after me: ‘I, Mei Lin, freely offer this card to the Great Sage for him to inspect, to judge, and to return as he sees fit, and in doing so I gain the benefit of being known as the one who mapped him.’”

Mei Lin’s eyes narrowed. “Why would I say that?”

Sun Wukong tilted his head. “Because it’s true. You do gain that benefit. And because you are proud enough to want it said aloud.”

Mei Lin hesitated, then said sharply, “No.”

Sun Wukong sighed, as if disappointed in her. Then he lifted the card again, angled it toward the candlelight, and spoke to it as if to an old friend.

“Little shadow of mine,” he said, “tell her: if she refuses to let me inspect, I will go tell every fox spirit and mountain ghost in this city that her mapping is sloppy.”

Mei Lin’s eyes widened. “You wouldn’t.”

Sun Wukong’s smile was bright as a blade. “I would. And the worst part is, I would tell the truth in a way that sounds like a lie. That is my specialty.”

Mei Lin’s jaw clenched. She glanced at the other cards in her book—her trophies, her proofs. Reputation mattered to such a one as she.

Finally she said, through her teeth, “Fine.”

And she repeated the words exactly as he gave them.

The air tightened. The image on the card shimmered. For an instant Mei Lin’s gaze unfocused, as if a thread had been tugged behind her eyes.

Sun Wukong’s finger slid across the card’s surface—softly, like stroking fur—and something cold and bright snapped into his palm, invisible to Mei Lin: a grain of essence, his own spark, neatly unknotted from hers.

He did it without tearing paper, without shattering magic, without spilling anything. A theft so clean it looked like a blessing.

Mei Lin blinked. “What—what did you just do?”

Sun Wukong held up his empty hand. “Inspected. Judged.”

Mei Lin glared. “You took something.”

Sun Wukong’s eyes danced. “I took what was mine. And because you promised I would return the card as I see fit…”

He paused.

“…I will.”

He placed the card gently back into the spellbook’s slot, exactly where it had been.

Mei Lin froze. “Why didn’t you keep it?”

Sun Wukong leaned back, hands behind his head, looking entirely at ease in a mortal room. “I recovered it.”

Mei Lin’s brow furrowed. “But it’s still here.”

Sun Wukong’s grin returned. “Paper can stay. Essence cannot be held by paper unless the owner allows it.”

Mei Lin’s expression shifted—annoyance, respect, dawning comprehension. “So, you came for your half.”

“Not even my half,” Sun Wukong corrected. “My grain. You can keep your grain. You can keep your method. You can keep your pride. I have no need of those.”

Mei Lin stared at him. “Then why let me keep the card at all?”

Sun Wukong’s face softened into something almost wise. Almost.

“In the old journey,” he said, “there were eighty-one trials. Every demon wanted the monk’s flesh, and every god wanted to pretend he was not involved. I learned then that the world is full of eyes—some sharp, some foolish, all hungry.”

He tapped his temple. “If there is only one Sun Wukong, every eye looks for him. If there are many—shadows, echoes, mapped selves—then the eyes must chase the wrong monkey half the time.”

Mei Lin listened, silent.

Sun Wukong continued, “Also…the world grows dull. The heavens are orderly. Humans are busy counting money. If a clever girl in Beijing wants to let a little Sun Wukong loose from time to time to stir things up…”

He shrugged. “Who am I to stop her? Too much order makes rot.”

Mei Lin’s lips almost smiled. “So you’re giving me permission.”

Sun Wukong held up a finger. “Not permission. Guidelines.”

“I’m listening.”

Sun Wukong’s tone turned brisk, like a general laying down rules for undisciplined troops.

“One: You may summon my mapped self only against creatures that prey on the weak—bullies, liars, and those who fatten themselves on fear. Two: You may not use it to gain wealth. If I smell greedy hands, I will bite them. Three: You will never claim you own Sun Wukong. You may claim you met him. You may claim you survived him. But never that you own him.”

Mei Lin’s eyes narrowed. “And if I disobey?”

Sun Wukong’s smile was bright and dangerous. “Then I will return and map you.”

Mei Lin stared, then laughed—a short, surprised laugh. “You can’t. You’re not a caster.”

Sun Wukong leaned forward, eyes gleaming. “Little Plum-Forest. I am Sun Wukong. I am whatever the story needs me to be.”

Mei Lin’s laughter faded into a grin of respect. “You still didn’t answer your own riddle,” she said.

Sun Wukong stood, stretching like a cat. “I did. Just not aloud.”

Mei Lin lifted her spellbook slightly, guarding it like a chess player guarding a queen. “Then tell me now. What are you, now that you’ve been mapped?”

Sun Wukong paused at the door. The night wind slipped in, carrying the scent of cold stone and distant roasted chestnuts.

He looked back at the card one last time. The mapped monkey looked back at him, eyes full of mischief, like a younger brother eager to cause trouble in his name.

Sun Wukong’s expression turned—briefly—tender then amused.

“I am,” he said, “a lesson.”

Mei Lin frowned. “That’s not an answer.”

Sun Wukong winked. “It is the only one that stays true.”

Then he sprang upward, and the room seemed to lose him the way a pond loses a fish: one ripple, and only silence.

Mei Lin stood for a long time afterward, staring at the card.

Finally she murmured to herself, half-annoyed, half-delighted, “Even when you lose, you win.”

From somewhere far above, as if the moon itself had learned to laugh, came a faint sound—mischief wrapped in wisdom—carried on the winter air.