Can’t Go Home Again

Terry Krakower got a letter from the lawyer in his post office box. It was the exact kind of letter that had prompted him to get a PO box in the first place—if they knew where he lived, they’d be banging on his door with these kinds of threats.

Mr. Krakower, it read, your interest in the LFM has been brought to our attention, and though this letter is intended as only an enquiry, we are prepared to take actions as necessary to protect a civic mascot if your intentions are disreputable. We have reserved an appointment window for you on Thursday, the 22nd, between 7:00 and 8:00 a.m. This meeting will entail no cost to you….

Et cetera, et cetera. It was on letterhead stationery and was signed Aaron F. Vegdon, LL.M. Krakower knew his legal acronyms—LL.M. meant Mr. Vegdon had a master of laws degree. That made this letter the foundation for a cease-and-desist order. And LFM was a shorthand way of disguising the absurdity that Vegdon wanted him to stop looking for the Loveland Frogman.

Yeah, right.

Skipping breakfast, Krakower was deliberately early for the appointment with Aaron F. Vegdon, Esquire.

Loveland Avenue in downtown Loveland was completely empty so early on a weekday morning—most of the businesses opened at ten o’clock or later. He parked across the street in front of an empty shop with dark windows marked with soap and noted the city sign about a two-hour parking limit.

“Half that time,” he said aloud; he had no reason to speculate that the city would end up towing his Toyota when he failed to come back for it for two days. They’d find the empty gun holster at the impound lot.

The address included in Vegdon’s summons—because, Krakower knew, that’s what it really was—was upstairs on a second story above a bistro and a restaurant. He took the steps two at a time and found the office based on its number; there was no signage, but the door was unlocked, so he let himself in.

The waiting room had a receptionist’s desk and a single office chair, but no one was there. The walls were empty, and the overhead lights were off. Had it not been for the man who emerged from the inner office, Krakower would have thought the place was as abandoned as the business across the street. Downtown Loveland wasn’t impressing him with its robust economy.

“Mr. Krakower, sir,” the man said, extending a hand. He had a speech impediment on his S. He was older and short, both of which pleased Krakower, but he was also stocky, which made him wonder if Vegdon had been athletic at any point in his life. Athletes, he knew, were more difficult to browbeat. They usually had it in their heads that they could win through physical intimidation or even violence. Vegdon, though, was maybe too old for a beatdown—he wore a wool Irish cap, the kind Krakower associated with elderly golfers. It spoke volumes.

Krakower held up the letter, rejecting the handshake. “Civic mascot, Vegdon? You’re accusing me of stalking the Brownie Elf? Slider? Moondog?”

Vegdon withdrew his hand. “Those are all Cleveland sports mascots. Men in costumes. Come inside.”

The inner office was as vacant as the waiting room: a desk, one chair behind it and one in front of it, and a doorless closet with Vegdon’s overcoat and walking stick. The lawyer went around the desk to sit, and Krakower noted he was wearing a gray vest.

You know who wears vests? Cowboys, groomsmen, and lawyers.

Krakower considered standing for the entire conversation, all of forty-five minutes maybe, but he had a few things to say, and he didn’t want Vegdon to look away if Krakower towered over him. He’d get down to eye-to-eye. He sat.

“You don’t live in Loveland.” Vegdon stated it; it wasn’t a question.

“No, I don’t live in Loveland. Not anymore. I live on the other side of Cincinnati now.” He looked around at the bare white walls. “Your law degree must be hanging on your mother’s refrigerator, huh?”

“We’re in the middle of moving. Across the river, closer to the courthouse. Tell me, what is your interest in the Loveland Frogman?”

Krakower snorted. “Right to the point. Okay. What’s your interest in my interest?”

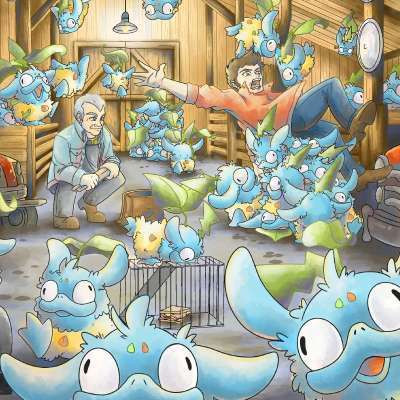

“We’re not sure how long you’ve been in Loveland or how long you intend to stay. But we’ve heard from some local business owners that you’ve been asking about the Frogman Festival.”

“I’m a party hound.”

“And whether the Frogman will be in attendance.”

Krakower laughed out loud this time. “I wouldn’t expect to catch it playing Frogger or watching Princess and the Frog in the park. I didn’t ask that.”

“So, you’re trying to catch it?”

Krakower’s face changed; fun and games were just about over. He let out an angry breath through his nose. “Nope. I’m trying to kill it.”

He could see that he had Vegdon’s complete attention now, but he could feel his own attention shift, back to memories. For a moment, he cursed himself for a missed opportunity—he now thought of a much more cutting response to Vegdon’s You don’t live in Loveland crack: No, but I almost died in Loveland. But you always think of something wittier when it’s too late. He resisted closing his eyes, but the dryness in his throat was beyond his control. He cleared it with ragged cough. “Let me tell you a story, Vegdon. What is that, Irish? Like your cap? I’ll keep this brief—I can see by your empty desk that you’re a busy man.”

Vegdon didn’t respond, and Krakower took the window of silence to organize his thoughts. “Eight years old. We lived out on Shore Road, about fifteen minutes by bike from the Loveland Castle. You know it, I assume? You ever tour it? It’s a real castle, man, just house size—but it’s all stone inside, turrets and parapets and the whole nine yards. The guy who built it based it on a castle he’d seen in World War I in France.

“I rode up there all the time while Andrews—the old man who built it and lived in it—was still alive. He was all alone in there, but for fifty years, he kept adding to it, doing nearly all the work himself. “Sometimes when I stopped at the bottom of its hill, I could hear him banging away in there, maybe a hammer on stone, constructing his castle, Chateau La Roche, brick by brick. I know he had visitors, but I never saw any of them or met him in person.

“He died one spring after he accidentally set himself on fire at the castle. He held on for a while, maybe a month, but in the end, he was pretty old. Quite a few stories were retold about him then, but the one that was new to me was that he had been declared dead before he went overseas. Meningitis killed him, but the doctors brought him back, blind and paralyzed. And then he recovered from those. So, the story I heard from kids at school was that Andrews might have been burned to death, but maybe he survived anyway. Maybe he was still in the castle.

“Kids explore. Especially boys. And especially only children. Houses with their windows boarded up or forgotten barns with saggy roofs or remote cemeteries with moss-covered mausoleums and weeds taller than the tombstones—they all have indescribable appeal to a boy to find out what’s there. It’s the lure of a haunted house. You just gotta see what’s left behind when the living abandon these places. You don’t think about rotted floorboards or what’s floating in the air that you might be breathing. When you’re a kid, you think about what you might discover waiting there in the half-light.

“And a castle where no one lives anymore? There was a song that spring with lyrics—‘while you see a chance, take it’—that I could hear over and over in my head like a mantra.

“When I went in, it was late afternoon. I put my bike in some bushes closer to the road and walked up the hill. There was nobody there, as far as I could tell. The sun was starting to set, so the stones were a dark gray, and there were deep shadows in the archway and tunnel I went through to get inside.

“I found out later that the castle had a dungeon, but I saw a rock staircase going up, and so I went that way. One floor up were tight little rooms, some of them not much more than circular chambers with a rough table in the middle, some of them long narrow halls with almost no light. I poked around in them, listening so hard for sounds of anyone else in the castle that my eardrums thrummed. I found another set of stairs, and in a short time, I found myself on the flat roof. The sky was getting dark. There were silhouettes of trees on three sides that hovered over the castle, leaning in like they were watching. At one end of the roof was another flight of steps that went up to the top of a short tower with battlements. I wanted to see the view. From there, you could look down over the whole of the castle grounds, even across the street to the Little Miami River. No cars went by on Shore Road, but I could imagine what I might have looked like to Andrews if he’d been on lookout up there when I went by on my bike down below.

“I heard a door clang shut, loud and near. It turned out there was someone else still in the castle that night after all. And in shuttering it up, they locked the iron gate that let out onto the roof. When I came down off the tower and ran back across the roof to the way I came in, I couldn’t get out.

“I didn’t care if I got caught—I screamed that I was there, that somebody had to come for me, that I was scared, that I had to pee. No one came. There were no lights that I could see through the barred gate. I couldn’t hear anybody, though a few minutes later I heard a car start way down the hill and drive off.

“I freaked out. I beat on the iron bars of the gate until my hands were scratched and raw. I screamed until I was hoarse. Over and over, I kept imagining someone discovering my corpse in the morning, curled up in a terrified little ball like an unborn baby by the gate.

“I thought maybe I could jump, but it was dark, and I couldn’t see what I might land on below. If it were stone, I’d likely break my legs, and then I’d die along an outer wall instead of on the roof.

“And that was when the Frogman came.”

Krakower paused and looked at Vegdon, who said nothing.

But that’s because it all makes perfect sense up to this point. What comes next, he’s not going to believe.

Krakower said, “I was sitting on the stone floor next to the gate when I heard it coming from the floor below. It was like someone slapping a wet dishtowel against the rock of each step as it came up them. And it was breathing heavily, deep damp gasps in and out, the way it sounded when my mom had the flu the previous winter.

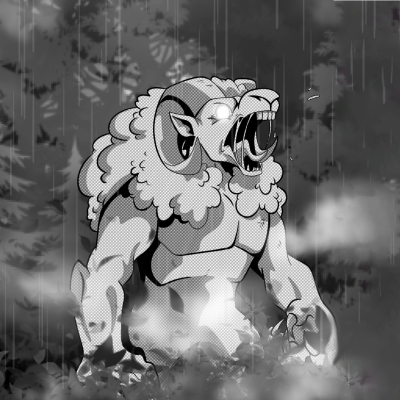

“I was too afraid to move. I pulled my knees in as tight as I could and scootched on my butt as far back into the shadows as I could, but I was sure it would see me. It appeared at the short flight of steps, a darker form against the darkness, a shape like a big pile of laundry. Then it jumped forward, up the entire length of stairs to the gate, and it slammed into the bars as if it didn’t know they were there.

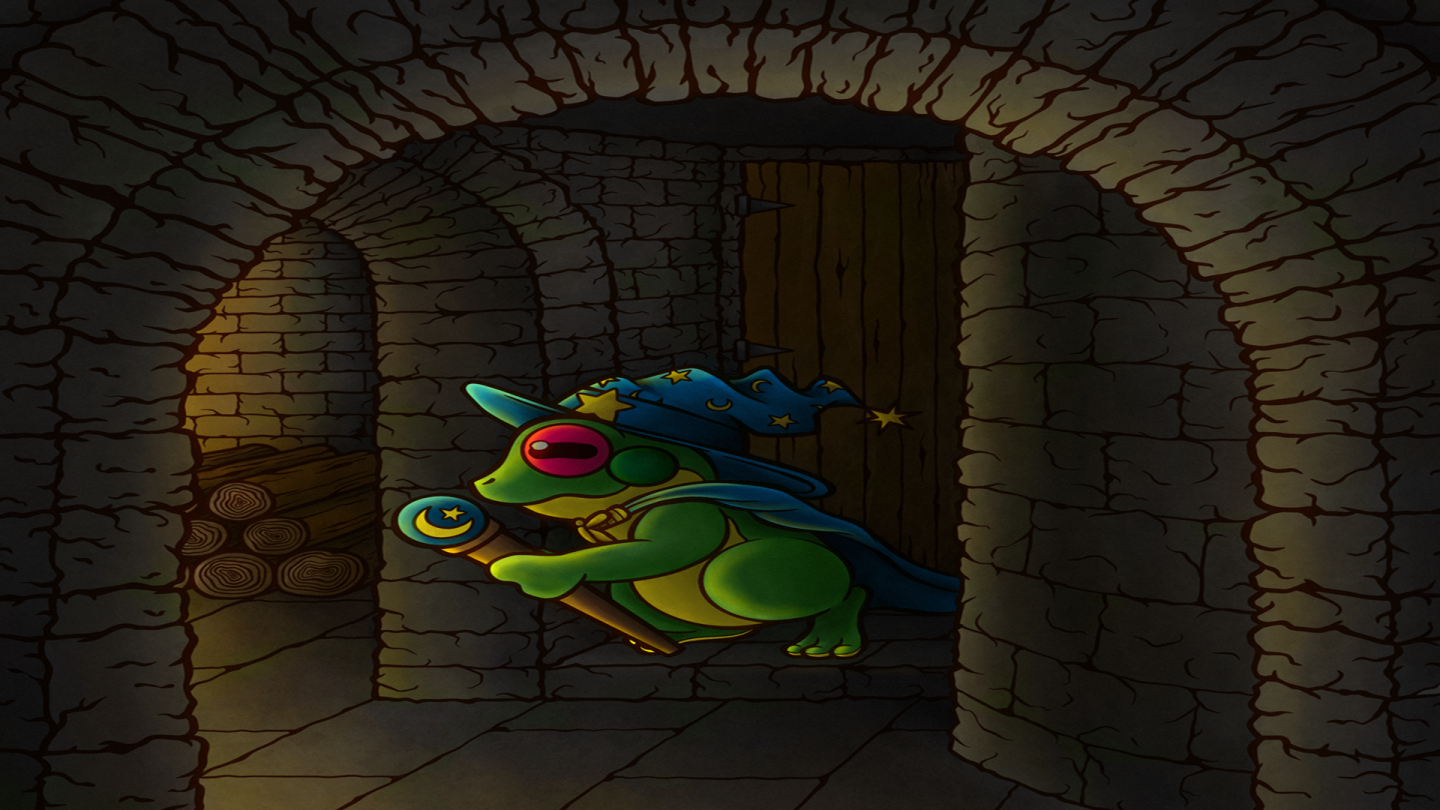

“I was two feet away from it at the most. It smelled like tomatoes gone bad. I was staring at one of its feet, which was bigger than mine—it had long, narrow toes, and sticky pads on each of them—when it shifted, they sounded like Velcro tearing free. Its flesh was green and splotched, and as I looked up its length, I knew I was looking at a gigantic frog, as tall as I was, walking on its hind legs like a person. Its head dipped down toward me, and I could see one of its eyes pointed at me—it was a big red circle with a black line of pupil. That eye sank into its head for a moment, three quarters of it disappearing when it blinked at me.

“But the worst part was that it was a frog in humans’ clothing. Ever see when people put their dogs in costumes so they look like little people when they run toward the camera? This huge frog was wearing a cape like a superhero and one of those pointed hats like Gandalf wears, and it had the toes of one of its forelegs wrapped around something that looked like a wand or a scepter with a big bluish ball on top of it. Like a hand holding a staff.

“I had no doubt at all that it had come to kill me.

“Then it touched the iron gate with that scepter, gurgling with its lips rolling from left to right, all Rs and Bs, and the gate—well, the gate, it just vanished. It disappeared like it had never been there. There was nothing between me and this hideous Frogman.

“A bunch of things happened all at once then. It reached for me with its empty hand or foreleg or whatever that appendage was. I let out a bloodcurdling scream at the top of my lungs. And a car horn started honking down on the street—my mom and dad had been driving around looking for me and had found my bike.

“Just like that, the Frogman was gone. It leaped over me and up onto the roof, and another leap took it over the ledge and into the night. I bolted down the stone steps, which were slippery and slick with some kind of grease or mucus, and out through the main tunnel and the archway onto the driveway. If there had been a front door in that archway, it was gone now. I could see my parents’ Oldsmobile at the bottom of the hill. My dad was standing by the driver’s side, reaching in to lay on the horn. My mom was calling my name with her hands around her mouth.

“As I was running down the hill toward them, I had this terrible thought: that the Frogman would emerge from the castle entryway behind me and that it would lash out with an impossibly long tongue, wrapping it around my waist. The last thing I would see before it yanked me back into its expanding mouth would be the horror in my parents’ faces as they watched it eat me alive. They would vanish from my sight when its lips closed over my face, and the acid that was its spit began to burn my skin off, and it swallowed me whole.”

Krakower stopped again, lowering his eyes from Vegdon so the attorney wouldn’t see the terror in his features. He clenched and unclenched his fists below the desk’s edge and licked his lips. “That didn’t happen, of course. In fact, nothing happened—not then. But later…

“My folks were all over me about going into the castle uninvited. My dad kept calling it ‘burgling’ and my mom told me over and over that it was private property. I didn’t say a word about the Frogman. I didn’t have to. The nightmares started the next night. My parents knew something had happened, just not what.

“Nine years. That’s how long I had nightmares about the Frogman. One or two a month. They always ended the same way. It would come up behind me someplace I felt safe—watching MacGyver on TV while my parents were upstairs, at the movies with my friends, running track after school. It would suddenly get very dark—the movie would stop or the sun would drop out of the sky as I finished a lap—and I would smell rotten tomatoes.

“Then three long toes would fold over my shoulders from behind, sticking to my shirt, and I would hear those Rs and Bs as it said something to me just before its mouth closed over the top of my head. I’d wake up screaming every single time.

“When I was in high school, I had a couple of buddies, Mel and Jay, who got this idea to go looking for the Frogman. Stupid teenager stuff. Camelot Cinema—a “walk-in” theater, they called it in the paper—just quietly closed up in the early ‘80s, so local kids had to find new sorts of entertainment. Jay reminded us how the city had converted the old railroad corridor a few years earlier, turning it into a bike trail, and he said because of that work, the Frogman had been displaced. It was extremely active now, and it was living in the woods along the Little Miami River. He said some other kids had seen it late at night, crossing the road to and from the water’s edge.

“I was only brave because they weren’t scared—I don’t think they had any idea what kind of a horror that Frogman was. When we got there, Jay produced pellet rifles from the trunk of his car. You couldn’t even kill a squirrel with these old guns, but holding one made me feel stronger. None of us were hunter types, but we trekked off into the woods anyway, trying to be quiet but probably alerting every living animal to find shelter until the Three Amigos were done blundering through the trees.

“We got separated almost immediately, and I remember thinking, We’re just like teenage idiots in horror movies. As soon as you’re by yourself, Freddy or Jason gets your stupid ass. Not three minutes later, the Frogman leaped past me onto the trail ahead.

“I was seventeen and had a loaded pellet rifle in my hands, but I was instantly eight years old and helpless again. I could see its eyes turn in my direction, and it still had that scepter it had carried all those years ago in the castle. I thought I could smell it, though it was too far away for that. But I knew that I was close enough for its tongue to grab me, if it wanted to. It could snap its tongue straight into my face, gluing itself between my eyes, and pull me into its mouth, headfirst.

“It looked at me and croaked something unintelligible. But I knew it was trying to speak.

“I got off one shot, but I don’t think I hit it, and it fled into the darkness of the woods. Only after it was gone did I realize I’d been screaming nonstop since it had first appeared on the trail. I just couldn’t stop. Mel and Jay were crashing through the woods somewhere not too far away, coming for me, shouting words I didn’t understand.

“Mel got to me first, and he was able to calm me down enough to stop screaming, but then Jay started to shout something new: Bear. He came charging down the trail, frantically waving us ahead, bellowing, “Bear! Run! Bear!”

“All three of us hightailed it back to Jay’s Fiesta parked at the trailhead, and he tore out of there as if the bear were right behind us. All the way home he jabbered. I sat shaking in the backseat, remembering all my nightmares about the Frogman as if I’d just woke from one, only half-listening to Jay telling us about the black bear he’d stumbled across not far from the trail.

“‘It was crazy,’ Jay went on. He was excited and panicked at the same time. ‘I saw a bear, man, right there. Who do you even call? And who puts a hat on a bear? Do we call the cops or animal control or the newspaper? Is there a reward? Maybe it’s somebody’s pet, you think?’

“I heard it all, but what I processed was the hat. The bear was wearing a hat, Jay said. A big blue wizard’s hat, the kind ‘you see in cartoons,’ he described it. Just like when it came for me at the castle, I didn’t say anything about seeing the Frogman again to my buddies. But I knew something else about it now: it could change its shape.”

Krakower stood up suddenly, stepping back from Vegdon’s desk. The lawyer looked up at him but stayed seated. Krakower paced a few steps away before returning to the desk, but he didn’t sit down again. No point now, not this far into the telling.

“The day I was old enough, I moved away from Loveland. I didn’t go far—my dad died when I was still in high school, but my mom stayed here, still on Shore Road, not far from the castle. I went to Cincinnati. She came to my house for the holidays, for birthdays, and I never had to come back here. She knew I couldn’t, I think. After a while, the nightmares stopped, and I even stopped remembering it. It got crowded in back there in the mental storage locker with so many other things piled around it that I’d have to go digging if I wanted to find it again. And I never went digging.

“At least not until Mom died last month. I was the last of the family—no other kids, no other close relatives. So, I came back to Loveland to settle her affairs and arrange the sale of the house. But as soon as I got here, it was like I never left. The nightmares started in again—I’d wake up in my old bedroom after dreaming I was eight years old and trapped on the castle roof while a black bear in a wizard’s hat came at me in a fury. I’d scream or cry and feel totally at the mercy of whatever memories my brain decided to torture me with the next time I was brave enough to sleep.

“That was when it occurred to me, Vegdon, that Wolfe was right: You can’t go home again. I think it’s the place where your dreams finally get laid to rest, but your nightmares find new ways to live. The Frogman was going to haunt me in Loveland or Cleveland or Ireland. If I wanted peace of mind, it would need to rest in peace. And now here I am, home again, to settle the last of my family’s affairs. My affairs. I’m going to kill the Frogman, and your piece of paper isn’t going to stop that.”

Vegdon seemed to process everything Krakower had said to him over the last forty-five minutes, but his expression had hardly changed at all. Krakower knew what the lawyer was thinking and what he was going to say even before the older man began to speak. When he finally started, Krakower swallowed his disgust.

“Mr. Krakower, I’m sure you’ve had some truly terrifying experiences growing up in Loveland,” he said, “but I hope you understand that you’re the exception to the rule. The Frogman is just a fun local story. Even if it were real, I don’t hear anything in what you’re telling me that suggests it intended to harm you. In fact, didn’t it help you get out of the locked castle? Listen to me. We have a Frogman Festival here in March. My grandson participates in the Ribbit Run. I have a crocheted Frogman on my desk over at the new office. What you’re going through is something that killing an imaginary mascot isn’t going to solve because, frankly, you can’t kill an imaginary being. It’s in your head, sir, and though I’m no psychiatrist, I think you can find a different outlet to deal with your childhood memories. Someone can help—”

“I don’t need help,” Krakower said. “I need to stop being afraid of a thing—a very, very real thing—that’s plagued me forty years. And I intend to do that. Right here in Loveland.”

“You’re endangering the local—”

“I got your letter,” Krakower cut him off again. “File a suit against me, counselor. By the time we get to court, this’ll be done.”

Vegdon slumped in his chair, and for a moment, Krakower felt sorry for him. A legal brief was no match for a pistol, even if the brief were in the right. Restraining orders only stop people who care if they get caught.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Krakower,” Vegdon finally said, his impediment changing the word to rorry. “I’m going to have to alert the police chief. He may very well choose to arrest you, I don’t know. I’ll argue that you’re not in a sound state of mind and that you may be armed.”

Krakower considered—only for a moment—going over the desk at the old man, but that would be a legitimate reason to have him arrested, so he held back. Instead, he said, “I guess I’ll see you in court.”

“Gandalf was more a father figure than a wizard,” Vegdon said. Krakower thought it sounded defiant, a gotcha that made no difference at all, just an unwillingness to be defeated entirely. “He was always pushing the others to move ahead. Nagged fatherly—that’s Gandalf the Grey, mixed up.”

“Well, you learn something new every day.” Krakower didn’t even say goodbye or good riddance. He simply exited the small office through its empty waiting room and headed down the stairs. It wasn’t quite eight o’clock yet. He would go back to his mother’s home from here, make himself breakfast, and then go hunting. He took out his car keys, considering the day, hearing his stomach growl, thinking of the lawyer’s parting shot, so smug.

Nagged fatherly, mixed up. A smarter retort would have been, mixed up like you, you mean. Mixed up like Gandalf the Grey.

Mixed up.

He frowned as he got behind the Toyota’s wheel, fishing in his pocket for the letter from the lawyer. Then he reached across, found a pen in the glove box, and clicked it over and over while he looked at the name.

Aaron F. Vegdon, LL.M.

He started crossing out letters, the paper held against the center of the steering wheel. The car horn accidentally honked once, making Krakower jump and swear.

Aaron F. Vegdon, LL.M.

He didn’t need to finish. He tossed both letter and pen into the passenger seat and reached into the glove box again. This time, he removed his Glock 44 and tossed the holster back in. He watched the windows to Vegdon’s office even as he checked the magazine. One car passed through downtown; he waited until it was well into the next block and on its way over the river before he got out.

Up the stairs, two at a time.

He opened the door gently, slipping into the waiting room and leaving the door open behind him for the sake of silence. When he got to the inner office doorway, he put his back to the wall so he could see partway into the room. Vegdon’s overcoat and walking stick were gone from inside the doorless closet.

He took off while I was sitting in the car, sorting out his stupid name riddle. He’s headed back to the woods.

To be sure, he stepped into the office and turned to look at the corner he couldn’t see from the waiting room. A shadow surged toward him.

For a moment too long, he was petrified. The red eyes with the black slits. The splotchy green skin. The horrible smell. The Irish cap had been replaced by a blue wizard’s—

Gandalf’s

—hat on the top of the creature’s misshapen head. The overcoat had become a cape, the kind a superhero might wear. And the walking stick had become a scepter with a bluish orb on top, the one he’d seen the Frogman carrying in the woods thirty years ago, the one he’d seen the Frogman use to make an iron gate disappear on the roof of the castle forty years ago.

The Frogman’s mouth turned down. It held out its scepter.

Raw-ree, it said. Rorry.

Sorry.

And the ball atop it touched Krakower’s arm just before he—