13: A Tale of Hat Man, or Buzz

It’s very hard to know sometimes what upsets the creatures that live in the world that cryptids see. They know we’re here, but they are no more interested in us than we are in fish when we go for an early morning swim. Yet sometimes they notice us. Sometimes we offend the serenity of their sea, and what’s down there in the darkness comes surging into the light long enough to break the surface and show us what’s just beyond our sight when we think we’re safe.

Only 989 tales to go.

Before I tell you what happened to Tina and me this weekend, I want to tell you something I learned when I was a kid.

My dad told me, “A man takes his hat off indoors out of respect. In medieval times, it was to prove he wasn’t concealing his face or a weapon. It came to mean honesty—‘I have nothing to hide.’”

I’m going to tell you what happened now, though you’re not going to believe me, and then I’m going to prove I have nothing left to hide.

***

Do you remember the TV show Lidsville? It was a Saturday morning live-action show—which means if you’re under forty, you probably don’t know what I’m talking about—about this kid who falls into a magician’s hat and ends up in Lidsville, where all the citizens are anthropomorphized hats. It freaked me out. It was Alice in Wonderland as imagined by Hunter Thompson. At six years old, I was especially scared of “Boris,” the executioner’s hood that carried around an axe. My older sister, Tina, who was almost ten, was more insulted that afraid—she thought the vampire hat was stupid.

“Vampires do not now and never have worn hats,” she complained to our dad. That gave me relief, her logic. She smiled at me. “Don’t be a sissy, okay? Dad knows it’s stupid, too.”

He was a consultant on the show, believe it or not. He owned a hat shop that he ran out of the front parlor of an old East Coast house we moved into in the late ’60s, and he befriended one of the producers of the show who apparently collected hats—which our dad did, too. His prized piece was a hat Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson offered to Robert Frost to shield the poet’s eyes from the sun so he could read a poem at JFK’s inauguration. I knew that story by heart by the time I was five, though I couldn’t have picked LBJ, Frost, or JFK out of a lineup.

But I sure knew that hat.

Dad died last month—he was old, lived alone above his hat shop, and his neighbor found him. When they called us, they didn’t offer any cause of death. I got to town first, Saturday afternoon, and by then, the medical examiner had already released his body to Swinkel Brothers Funeral Home. I let Tina know, and she met me there.

“He was eighty-six,” the funeral director told us by way of explanation. “Sometimes we just shut down.”

It never occurred to either of us that he had been murdered.

***

The Dam Hatter was the name of my dad’s shop—it was in an old-school New England house that had been converted, so you stepped off the sidewalk and directly into the parlor that ran the entire width of the house. In New Barnsley, with a population of only 20,000, the Dam Hatter was maintained by goodwill. The heyday for headwear had come and gone long before Dad was even born, so most of his business was online. But the people of New Barnsley knew Wilford James as a good man, a longstanding entrepreneur who did magic tricks for local kids and had an old connection to Hollywood. He even had a monitor mounted above the register that ran episodes of Lidsville over and over. So, they bought hats that likely went straight to closet shelves.

It was like Tina and I had never left. We arrived just after dark on Saturday—yesterday—and my muscle memory knew exactly where the old light switch was. The parlor—the store—was elegant in a way only a private shop operated by an eccentric, amusing old person can be. You don’t really think about how many different kinds of hats there are until you’re confronted with the variety of fedoras, bowlers, and gatsbys available (Dad sold a gatsby online to a member of the band AC/DC one year and clucked, “He called it a newsboy cap.”) Among the traditional headwear were a beanie or two, a Sherlock Holmes hat (a deerstalker, officially), and lots of cheap Halloween costume hats, which were his bestsellers. There were shelves and stands and racks and hooks. The floors were still hardwood with no throw rugs to make it “gauche,” as Dad said always. More than anything, there was the smell of class and promise and Dad.

They’d found him in his bed upstairs, so we ventured up there with a hesitation born of the inability to imagine what you might see. The narrow stairs creaked as they always had. The hall light still flickered from tired wiring as it had decades ago. But his bedroom had nothing familiar or foreign about it—it was just a room under the roof’s slant. The curtains were drawn. He was never tidy, so there were clothes tossed on the chair and on the ottoman bench at the foot of the king-sized bed. The sheets were thrown aside on his side, where he slept still even though Mom died almost twenty years ago. I imagined whoever had found him pulled him out from under those sheets that had become shrouds.

On the floor beside Mom’s side was the top hat that had belonged to LBJ, Dad’s treasure. It belonged down in the shop under glass, but here it was, casually dropped, even cast aside.

“Maybe he was sleeping with it,” Tina said. She smiled at me as she picked it up; she was a jeweler, and she had a loop around her neck the way another woman would wear a diamond. She gave the hat a quick scan with it. “But it looks okay. Hopefully there’s still paperwork for it. Unless you care, I’ll find a buyer for it.”

I said sure, whatever you think is best, you know business, blah, blah, blah. I was noticing a Santa hat on the floor between the bed and Dad’s nightstand. Tina was already walking out, still talking, so I instinctively followed her, but I kept thinking: It’s August. And we’re Jews. Why was he keeping a Santa hat in his bedroom?

***

Was it our arrival, turning on all the lights in the Dam Hatter again? Was it finding the LBJ top hat or seeing the Santa hat? Was it Tina’s suggestion that she would sell that top hat? That, and my acquiescence. That’s what I think it was.

The doorbell—the buzzer, really—sounded shortly after ten o’clock. It buzzed, and it was a pretty angry sound, to be honest.

We were sharing a bottle of wine in the kitchenette at the back of the house and talking about old days and the dreaded days to come when we would have to close the Dam Hatter, so by the time we got up front, the delivery truck was long gone, but the package had been left leaned up against the side of the house right next to the door. It was about six feet long and narrow. When we got it inside, Tina magically produced a tiny razor blade with a handle—a jeweler’s tool, she said—and cut the box open.

As she was pulling back the cardboard as if she were opening the doors of a closet, I said, “There’s no labeling on this. No address, no return address, nothing.”

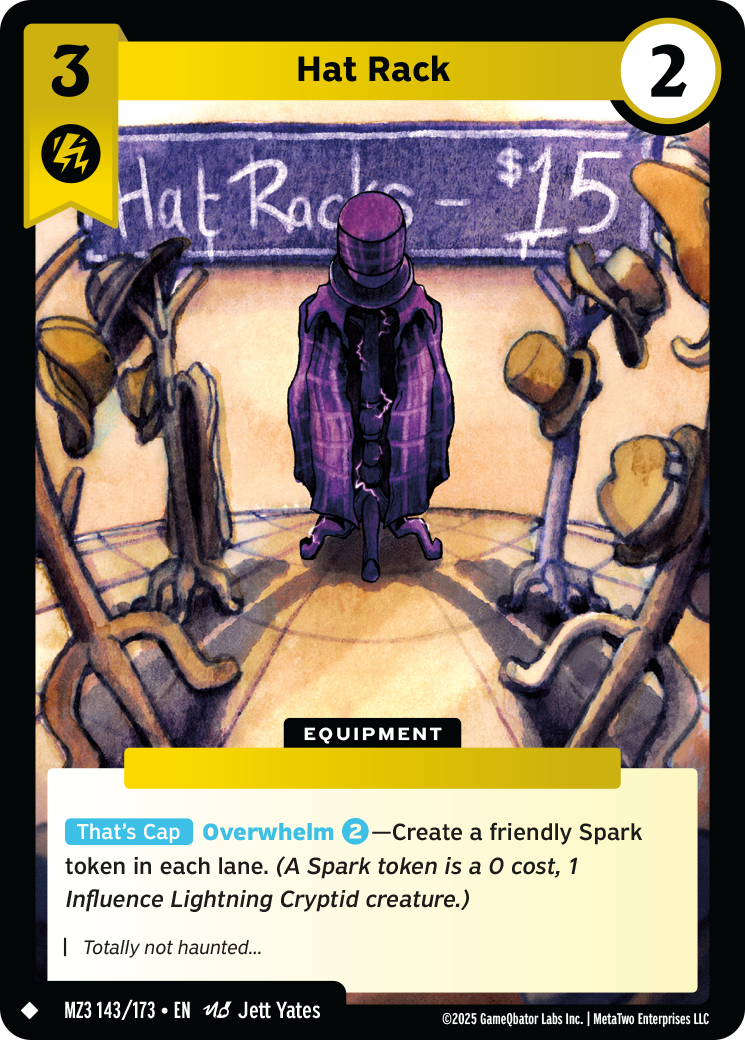

Inside was a hat rack, closer to a coat rack, I thought: a six-foot-tall central post with a circular base and a small golden orb on top. Some assembly required, which Tina did with ease. At irregular intervals around the post were a half-dozen hooks that extended off of it like branches from a tree. While they were uniform, they still struck me as malformed, as if they’d been melted by mistake and tossed in the box anyway.

“Don’t,” I said to her as she twisted the last one on. “There’s no reason to put this thing together, not if we’re going to shutter the business. Those hooks look like hands.”

She stepped back, and as she’d been when I was afraid of Boris the executioner’s hood and she was annoyed by the vampire hat, she said just the right thing to comfort me.

“Don’t be a sissy, little brother. If it tries to grab you, I’ll take it apart again.” She then pointed a finger at the hat rack, which she had stood by the entrance. “Pay attention. I have a screwdriver, and I know how to use it.”

That was good, and I appreciated it. I felt relief for the last time in my life.

***

Neither of us were going to sleep in Dad’s bed, of course, so Tina took the second bedroom upstairs, which used to be hers anyway, and I took the bedroom-cum-office on the ground floor down the hall from the dining room that had been converted to hat storage over the years. There was a daybed in there, and it would do for the one night. Tomorrow night, I planned to stay at the New Barnsley Comfort Inn.

I found some sheets but no blankets and a very hard pillow in a hall closet. I took them into the office, and when I flipped on the light, there was Dad’s LBJ top hat, under a bell-shaped glass dome. On the desk was the certificate of authenticity Tina had been talking about. I was glad she’d found it but surprised she’d not mentioned it to me.

It was still dark outside—3:30 in the morning, it turns out—when I heard Tina scream in sheer terror. It was shrill and long as echoed off the hardwood floors and oaken handrails and in and out of the head openings of a hundred hats. I stumbled out of the back, around the wooden counters, and up the stairs.

I did not notice that the new hat rack was no longer by the front door.

I tripped in the dark, memory refusing to remind me how many steps there were, and when I got to the top, I was disoriented for a minute. Then I heard a thudding noise to my right. Tina’s old bedroom was that way. Her door was open, and I reached around to find the light switch.

Something brushed my fingers in the dark. Something wooden but sharp.

I yanked my hand back, and in doing so, flipped on the light.

The hat rack stood right next to the door, beside the light switch, as if it belonged there. Atop the golden orb was a top hat—not the LBJ one, which I remembered seeing in the office as I came out. No, this had to be the one that was on the floor in Dad’s bedroom. It topped the hat rack as if it were a formal gentleman putting on the ritz, its six hooks out and spread like jazz hands. The top hat gave the shape a head where none had been before, and my heart hammered as I turned away from it, expecting to feel its hands on the back of my neck.

Tina was on the bed, face-up, staring straight into the bright overhead light that should have blinded her enough to blink. But she didn’t blink. One hand was a fist in the sheets; the other was a fist in a purple beret that covered her nose and lips and seemed to be at least partially jammed into her mouth. It could just as easily have been a Santa hat. Her pupils were already dilated. I fell to my knees beside her, yanked the beret away, and put one finger under her nose to feel for breath while I searched for her pulse with the other. I felt neither one.

A wood against wood sound made me turn toward the door. I don’t know what I expected to see— actually, maybe I do, but I didn’t see anything. There was nothing there—because the hat rack was gone, too.

I heard a series of thunks as it descended the stairs.

***

I finally ventured downstairs to call for help—my cellphone was here in the parlor—but now it’s nowhere to be found. It was here, charging, when I went up the stairs to find Tina suffocated as I strongly suspect Dad had been, but now there’s just the cord. The LBJ top hat was on the bed, though, the glass dome broken and on the floor, the hat beckoning to me like a prayer book. With my hands shaking, I picked it up and carefully put it on.

“I won’t sell it,” I whispered. “I won’t take it off. Just go. That’s all I ask.”

The shop-cum-house was silent. And it still is. But I don’t think it will be for long, because I don’t know what to do except what I’m going to do.

I’ve been writing this for the last 45 minutes, waiting for the sun to come up, but it hasn’t yet. With my phone gone, I’m not sure what time it is, but the sky’s not lightening, and I wouldn’t know where to go even if I were to leave the house. The LBJ hat keeps sinking over my eyes; my head is too small for it. I have to go to the bathroom, but maybe that doesn’t matter either. I don’t want to be a sissy. So, I found a screwdriver in the office desk’s drawer, and now I’m just about done writing.

There. I took the hat off.

There.

Now I can hear the doorbell buzzing. And buzzing. And buzzing.

It’s buzzing to come back in.

It forgot its hat.