14: A Hint of Chase Born, or “The Wendigo”

I have recently revisited a question I asked an old friend many years ago when I was in my youth: Are there any good casters? And by “good,” I did not mean “talented”; I asked in terms of morality. His answer was not reassuring.

Recently, I have been reviewing a host of stories I have in my possession about other casters, and I have found myself drawn over and over again to those tales that expose the darker underbelly of our profession. A good caster may well confront a bad one; a bad caster may well confront anyone.

And as stories are built on conflict, the bad casters thrive on it.

What follows is a simple paper from a college class held many years ago—when I was still in my eighties, in fact. What makes it interesting is that the author was even then a caster, and he revealed deliberately one of the myriad ways casters find the cryptids they intend to map: research. The irony here is that he opted to garner a grade for it at the same time.

If you are curious: He earned an A.

Yet I wonder how many others he lured to Maine as a result of his research.

Only 987 tales to go.

The Wendigo in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary: Folklore, Place, and Investigative Observations

Chase Born

University of Texas at Austin

Monsters in Modern Lit / E 352M

Dr. Joseph Kipper

Date: October 4, 2004

Introduction

Stephen King’s Pet Sematary (1983) is often assumed to be fiction, but for those attuned to patterns in both folklore and landscape, it might also serve as an unintended field guide to a monster. King’s novel draws heavily on the Algonquian myth of the wendigo—a creature of hunger, taboo, and transformation—and situates it in Maine’s geography, King’s favorite stomping ground. Close analysis suggests that King’s narrative may actually encode the spatial and environmental clues necessary to locate actual manifestations of the wendigo.

This paper investigates the wendigo as both myth and potential presence, exploring four dimensions: (1) the creature’s origins in Algonquian folklore, (2) King’s adaptation and spatialization of the myth in Pet Sematary, (3) my own field-based observations of locations described or implied in the novel, and (4) the wendigo’s recurrence in modern culture. Throughout, I approach the subject as both a scholar and field investigator, presenting evidence that King’s novel may provide practical insight into locating the cryptid known as the wendigo. (For the uninitiated, Merriam-Webster defines a cryptid as “an animal [such as Sasquatch or the Loch Ness Monster] that has been claimed to exist but never proven to exist.”)

The Wendigo in Algonquian Folklore

The wendigo originates in Algonquian-speaking traditions, including the Ojibwe, Cree, and Innu tribes (Britannica, 2025). It is associated with winter, starvation, and cannibalism, representing both external threats and internal corruption (Research Starters, 2025). Individuals who violate social or ethical taboos risk “becoming” wendigo, a transformation of one’s body and mind, something akin to the modern skinwalker or werewolf concept. In this sense, the creature is both environmental and moral, a warning encoded into the landscape itself.

Blackwood’s The Wendigo (1910) codifies many of these characteristics in English-language literature: a gaunt, predatory entity stalking the Canadian wilderness, preying on hunters. Blackwood’s work provides the template for a creature that is simultaneously ecological, psychological, and moral (Blackwood, 1910/Project Gutenberg). These attributes form the foundation for understanding King’s specific adaptation: the wendigo is never fully seen in King’s book but exerts influence through the soil, the air, and the perceptions of the main character.

King’s Spatial Adaptation in Pet Sematary

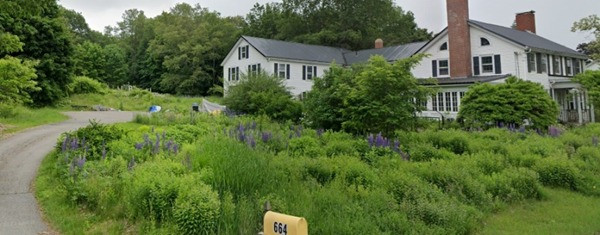

King situates the narrative around the Creed family’s home in Orrington, Maine—664 River Road—adjacent to a wooded area containing a child-created pet cemetery (Maine Public, 2017). Beyond this, a burial ground rooted in Micmac tradition introduces a site where death can be manipulated, the premise of the novel. King’s text emphasizes environmental cues: “a loathsome, carrion stench” (King, 1983, ch. 32), “the voice of the windigo [sic]” (ch. 33), and “the ground is sour” (ch. 35). These are not merely atmospheric; they are consistent with patterns noted in wendigo folklore, suggesting that disturbances in soil, odor, and sound may very well mark the creature’s presence.

King himself acknowledges the disturbing proximity of these ideas to his life (Entertainment Weekly, 2019). For a trained observer, however, the narrative encodes both spatial and sensory information: the alignment of home, road, and burial sites, all tied to death and then combined with the persistent influence of the woods, may serve as practical guidance for anyone willing to venture forth to find evidence of the wendigo.

Field Observations: Orrington and Bangor

Visiting 664 River Road, I approached the woods behind the property with the expectation that environmental anomalies might reveal themselves—I was braced for the presence of something evil. The undergrowth is dense, with irregular depressions, gnarled roots, and patches of mossed soil, consistent with descriptions of “sour” ground in King’s novel. Several weathered gravestones, likely remnants of children’s burials, mark minor clearings. Soil disturbances near these markers suggest repeated activity, either by animals or, potentially, by the cryptid itself. Subtle tracks appeared too large for known wildlife; impressions in soil, combined with snapped twigs, suggested movement that is difficult to attribute to natural causes.

Mount Hope Cemetery, Bangor (1048 State St, coordinates 44.82306, -68.72400), provides a secondary observational site. The mature evergreens and uneven topography there create pockets of shadowed ground consistent with areas where unusual phenomena might persist. Observations included areas of disturbed soil, unusually strong odors of decay, and subtle pressure differences in the air, consistent with historical reports of wendigo-like activity in northeastern forests.

These sites suggest that the novel’s depiction of burial grounds might be more than fiction. King’s narrative consistently aligns with environmental indicators that a trained observer can detect: soil disruption, olfactory cues, and faint acoustic anomalies. Reading Pet Sematary alongside field observation allows for triangulation of likely locations of supernatural presence.

Figures / Maps